Georgie Wileman - Endometriosis

WORDS BY ALICE ZOO

In one of Georgie Wileman’s self-portraits, she lies curled into a hospital bed, table beside her covered in miscellaneous hospital detritus — medications and polystyrene cups — and she stares blankly towards the floor. It takes a moment to notice that the phone behind her, towards the edge of the frame, is balanced upside down, off the hook. She will not be receiving any calls.

This elegant detail is a potent metaphor for the solitude at the heart of Endometriosis, a project that documents Wileman’s experience of the condition over a period of nine months. With the aim of unveiling the realities of this invisible illness and raising awareness of its trauma, Wileman initially intended to document the lives of other sufferers but was prevented from doing so by her own pain. Instead, the project is personal and inward-looking, allowing the viewer a searing window into the experience of this disease.

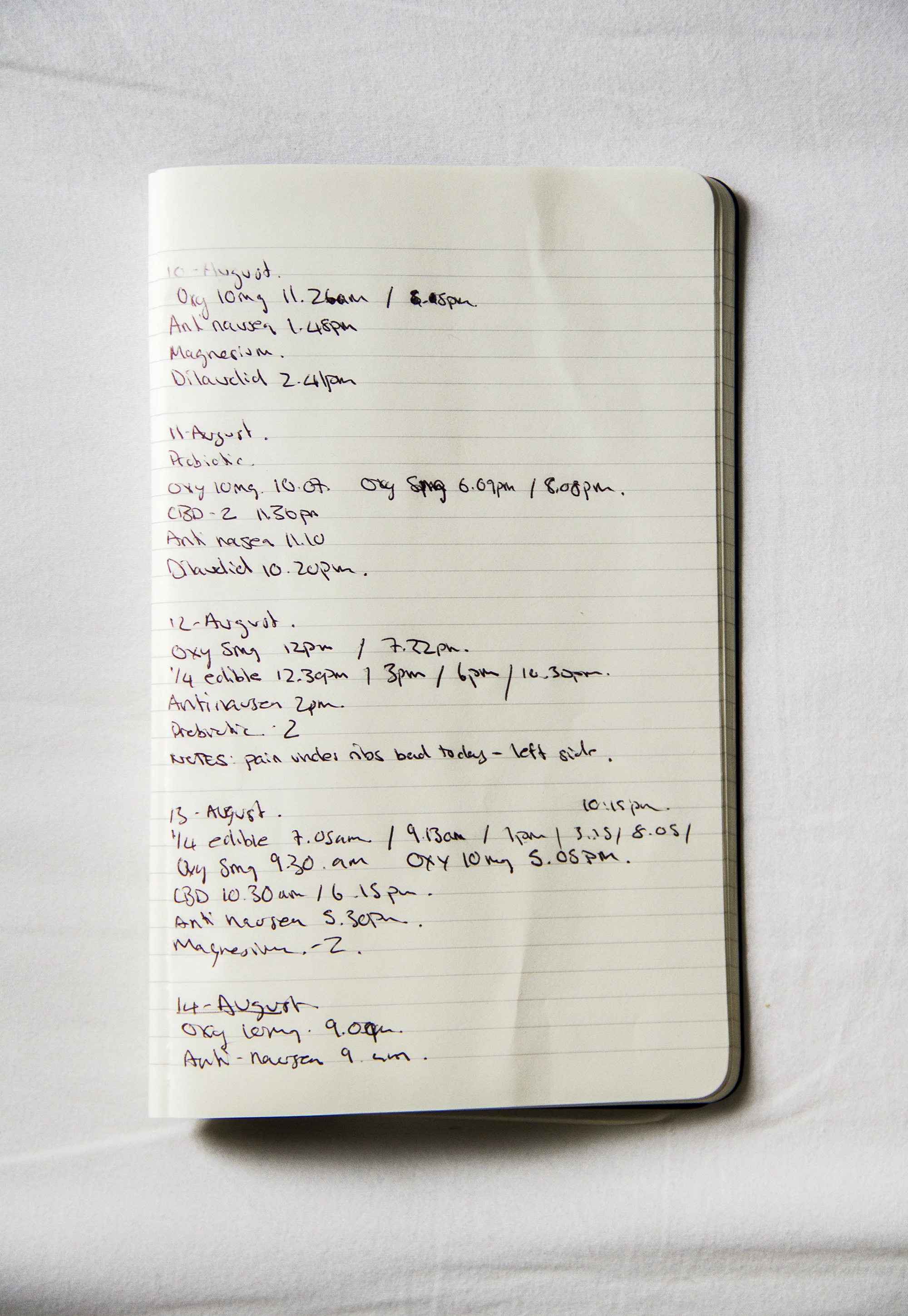

In lieu of being able to visualise the experience of pain itself, the project is full of symbols of the pain Wileman experiences. A wheelchair waits by the side of the bed. A bag of weed, a grinder and some papers lie on a bedsheet (the packet of papers reads: “Are you satisfied with the life you’re living?” — Wileman is adept at applying this kind of subtle gut-punch). When Wileman’s hands appear, they are twisted, tense and grasping, never at ease; the ever-present bedsheets and duvet are wrinkled and creased, suggesting the tossing and turning of the body in pain, as though the bedding itself has taken on its memory. We can witness the pain — we flinch at the more difficult images, the gauze and tissues around a seeping stain of bodily fluid — but we cannot feel it. It lies just out of reach of understanding or visualisation. “Photographing my pain has made no difference to my relationship to it. The physical pain can become everything you are, there’s no space to understand your feeling towards it in those times. If anything, having a physical memory of the pain makes it harder to forget,” says Wileman. While for the sufferer, the pain is all-consuming, for the viewer it is impossible to understand, and the gulf between the two is the underpinning for Wileman’s project.

The series makes use of cool, pale tones: bright washes of blue, yellow, beige and grey. Often, projects about pain or suffering are dark, shadowy. Endometriosis is a notable exception. The series is full of light and air, which makes its context even more jarring, harder to turn away from. “The beige walls and white sheets of my home were reflected at each appointment and in-patient stay. I wanted this series to show the mundane repetitiveness of this disease, the blur, the loss of time. To me these colours also speak of the sterility and isolation,” describes Wileman.

By the end of the series, the viewer feels a deep empathy, such is Wileman’s ability to communicate her wrenching isolation (she is, notably, the only human figure that appears in the series); the betrayal by her own body, abdomen covered in mottled bruising, swollen, patched in surgery-gauze; her vulnerability. Three of the images are taken of a blank wall, a shaft of light moving a little further across each time; by the third image, the light is nearly gone. We see the banality, the stillness of time, the way that the boredom of being permanently homebound results in being able to watch light’s journey across a wall, which might look beautiful if the context was one other than suffering.

“Creating something out of a desperate time, that may validate or comfort someone else in my situation, gave me purpose. Purpose is so important,” explains Wileman. But the project has its limits; it doesn’t offer salvation. The series is not necessarily finished. If Wileman has further surgeries, she will continue to document them. While we can turn away from the pictures, Wileman cannot. They are her daily reality.

The final image in the series is another self-portrait: the photographer gazing towards the camera with a close-up intensity that is profoundly ambivalent. Her eyes seem red from tears; they speak of pain, anger, acute vulnerability and self-revelation, and the force of a challenge to the viewer to look, to acknowledge, to try to understand.

This project was supported by the journalism non-profit the Economic Hardship Reporting Project.